In this opinion piece Stuart Milligan, Course Leader, MSc International Logistics and Supply Chain Management, University of South Wales-Dubai, contemplates the fast-changing dynamics of the logistics and supply chain landscape and what the scenario may look like when Covid-19 is behind us—Editor.

Post pandemic Supply Chain landscape

If you were to ask Chief Procurement Officers and Supply Chain Directors what the biggest risk to their organisations was twelve months ago, what would they have said?

A recent survey indicates that the top risks identified by organisations are: Fires or explosions; natural disasters such as earthquakes and wildfires; cyber threats; transportation disruptions; government interventions; and demographic shifts.

The Covid-19 crisis is more severe and widespread than any other supply chain disruption in recent history. Due to the vital role that the Middle East plays in global trade, connecting China with the rest of the world, supply chain disruptions have hit the region hard and have significant consequences for the rest of the world.

These disruptions are being felt within every mode of transport in the GCC. In air freight, IATA noted a 1.4% drop in Middle Eastern cargo volume in January 2020 against the same period last year, with a deeper decline forecast in coming months.

E-commerce on the upswing

In shipping, container ships are unable to dock at many ports due to Covid-19, and where they can dock, the crew are often not permitted to leave the vessel. In road freight, social distancing measures are causing a sharp rise in e-commerce, resulting in a shortage of distribution capacity.

For example, Bulkwhiz, a grocery e-commerce start-up in Dubai has seen a 100% increase in orders since February 2020 and are currently urgently recruiting additional delivery drivers to cope with increased demand.

Supply chain disruptions are commonplace; supply chain professionals are highly adept at expertly dealing with issues relating to continuity of supply or fluctuations in demand without the customer ever realising there was a problem. So, what is so different about Covid-19?

Simply stated, the current pandemic is so disruptive to supply chains that it has interrupted two of the ‘principal flows’ that supply chains require to work efficiently, namely, the movement of goods and the exchange of information. Covid-19 has highlighted the fragility of many global supply chains, so how can organisations manage supply chain risks and what might future supply chains look like as a result of Covid-19?

Risk management

Effective risk management should start with supply chain design. This is concerned with important strategic decisions such as facility location planning—which customers will be served from each distribution centre or factory, and which suppliers would be engaged, and more.

Typically, complex quantitative analysis is employed to calculate optimal supply chain structures based upon assumptions and constraints relating to demand, supply and transportation capacities.

Ideally, at this stage, organisations consider risks such as demand and lead-time uncertainty, and plans are put in place to minimize these disruptions. Practices such as vendor managed inventory, collaborative planning, forecasting and replenishment (CPFR) are common risk management techniques.

There are, of course, limitations with this perspective. Firstly, many organisations do not have the benefit of being able to design their supply chain in such a way. Their current infrastructure is the result of organic growth, legacy systems, and mergers and acquisitions, meaning that their supply chain design is sub-optimal.

Secondly, such measures are effective for day-to-day disruptions such as a single supplier experiencing a supply issue or a short-term fluctuation in demand, they do not equip organisations for a global crisis such as we are experiencing now.

The nature of supply chain disruptions

Supply chain disruptions are often categorized in two ways, the ripple effect (downstream) and the bullwhip effect (upstream).

The ripple effect is where disruption in the upper tiers of the supply chain ripple downstream resulting in a down-scaling of demand fulfillment in the supply chain, i.e. out-of-stocks ripple downstream ultimately to the customer.

To first explore this in relation to Covid-19, it is well documented that Covid-19 originated in China. China is responsible for 28.4% of all global manufacturing (Statista, 2020).

China spotlight

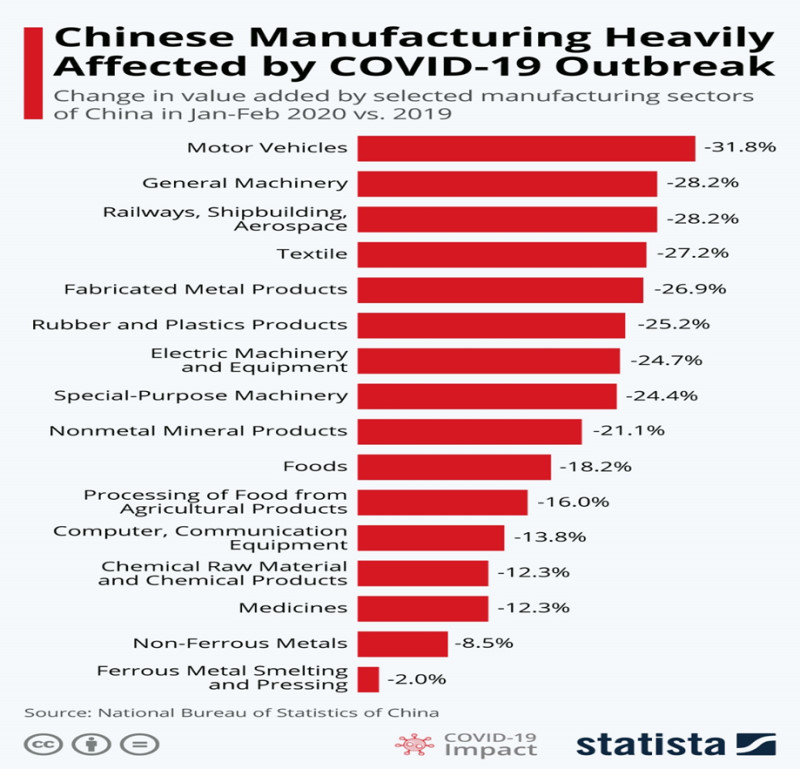

The infographic below details how each manufacturing sector in China was affected by Covid-19 in January and February this year. These are then shipped to a final place of assembly, ready to be distributed across the global marketplace. Global supply chains are complex, often with component parts being produced in many different countries to strategically balance capacity, quality and cost.

As an example, Apple works with suppliers in 43 different countries to make the iPhone, these components are then shipped to central assembly factories, predominantly in China, to be distributed across the world.

The 31.8% reduction in motor vehicle manufacture in China, experienced in January and February therefore didn’t result in motor vehicle not being manufactured per se, what it did result in, was an acute shortage of critical components that are used in the final assembly of motor vehicles.

As the virus spreads around the world, continuity of supply will become a bigger challenge, especially as other global manufacturing hubs such as the US (16.6% global manufacturing), Japan (7.2% global manufacturing) and Germany (5.8% global manufacturing) close their borders and their factories.

The Bullwhip effect

The bullwhip effect is where operational dynamics oscillate upstream, resulting in ordering oscillations. Simply put, as organisations experience shifts in demand, upstream suppliers alter their inventory holdings in attempts to meet potential new demands.

These inventory shifts tend to get bigger as the demand signal travels up the supply chain, ultimately leading to the severe over/ under stocking of lines. Covid-19 has been strongly associated with panic buying across the globe as society prepares itself with the challenge of social distancing and self-isolation.

Impact on healthcare and retail

This is a major issue for organisations and is felt most acutely by healthcare and retail supply chains. In the healthcare sector, the industry is desperately trying to understand the likely demand on resources as a result of infection, with demand for critical items such as face masks and respirators significantly outstripping supply.

From a retail perspective, social distancing is creating a surge in demand which is not only difficult to replenish, it is also difficult to forecast. The increase in demand for grocery products is so widespread that consumers often cannot find the products they want and are therefore choosing substitute products, inflating the demand forecast for these products and understating the demand forecast for the desired products.

Conversely in retail, there is an excess of non-food stock which would normally be in demand. For example, Noon.com are offering a 47% discount on the iPhone XS and 30%-45% discount across fashion lines in attempts to shift excess inventory. The Covid-19 crisis has forced consumers to adopt different demand patterns resulting in unplanned overstocks and stock-outs.

What does the future hold?

Whilst some organisations may fall casualty to the current crisis, the more resilient supply chains will survive. History tells us that some supply chains will recover faster than others; after the Japanese tsunami in 2011, the automotive industry was severely impacted.

Nissan in particular was less affected than its competitors. This is because Nissan had invested significantly in risk mitigation policies. Disaster recovery had become part of its culture; they had been conducting disaster drills for years to improve their ability to deal with disruption.

In response to the current crisis, organisations should become more collaborative, integrating both vertically with their supply chains, and horizontally with industry partners. Risk management and recovery is far more effective when it is approached collectively as an industry, rather than a single entity.

Stuart Milligan

Course Leader, MSc International Logistics and Supply Chain Management

University of South Wales-Dubai

Stuart Milligan joined the University of South Wales in 2016 and is the Academic Manager for Procurement, Logistics and Supply Chain Management. He is also the Course Leader for the MSc International Logistics and Supply Chain Management in the UK, and for the course at the Dubai Campus, which was introduced in September 2019.

Alongside teaching, Stuart is studying for a PhD. His research is based on the impact of adopting an omni-channel strategy, and his research interests include supply chain strategy, sustainable operations and the impact technology has upon the supply chain.